PRAIRIE GOLD

150 YEARS OF WEALTH THROUGH WHEAT

BY TREVOR BACQUE

Prior to Confederation, Canada already had more than 250 years of agricultural history to look back on from European settlers. However, that history was modest and the agriculture skewed toward subsistence, as opposed to the eye-popping crop yields of today. Twenty-five years before Canada officially became a nation, agriculture was being formed as a vital cornerstone of the country’s history and identity in rural Ontario.

David Fife was, by all accounts, your average Scottish immigrant. He came to Canada as a teen and farmed his whole life in Otonabee, ON, about two-and-a-half hours northeast of Toronto. He and his wife, Jane, a farmer’s daughter herself, worked hard to make their farm productive. Upon request, a friend of Fife’s had sent him a package of wheat varieties in 1841/42 that originated in Glasgow. It is widely believed that those seeds came to Glasgow by way of Danzig, now Gdańsk, Poland. Others posit the wheat originated even further east in the Galician region of Europe.

According to documented history, what Fife didn’t realize was that the variety was actually a winter wheat, which should have been planted in the fall. However, the Fifes planted it in the spring. Only three heads were produced, and a cow ate a generous chunk of that paltry crop. From there, only a few precious seeds survived. Those seeds were replanted the following year and the results were staggering. They yielded like no other, showed stronger resistance to rust—a fungal disease that farmers had no answer for at the time—and produced quality flour for bread making. The variety was dubbed “Red Fife” based on the distinct reddish tinge of the Fife family’s wheat fields.

It gave birth to a class of wheat you likely eat every day: Canada Western Red Spring wheat, known as CWRS or, more colloquially, “hard red.” This class and Canada Western Amber Durum, or CWAD, are our country’s two most vitally important wheats in terms of acreage and contribution to Canada’s GDP.

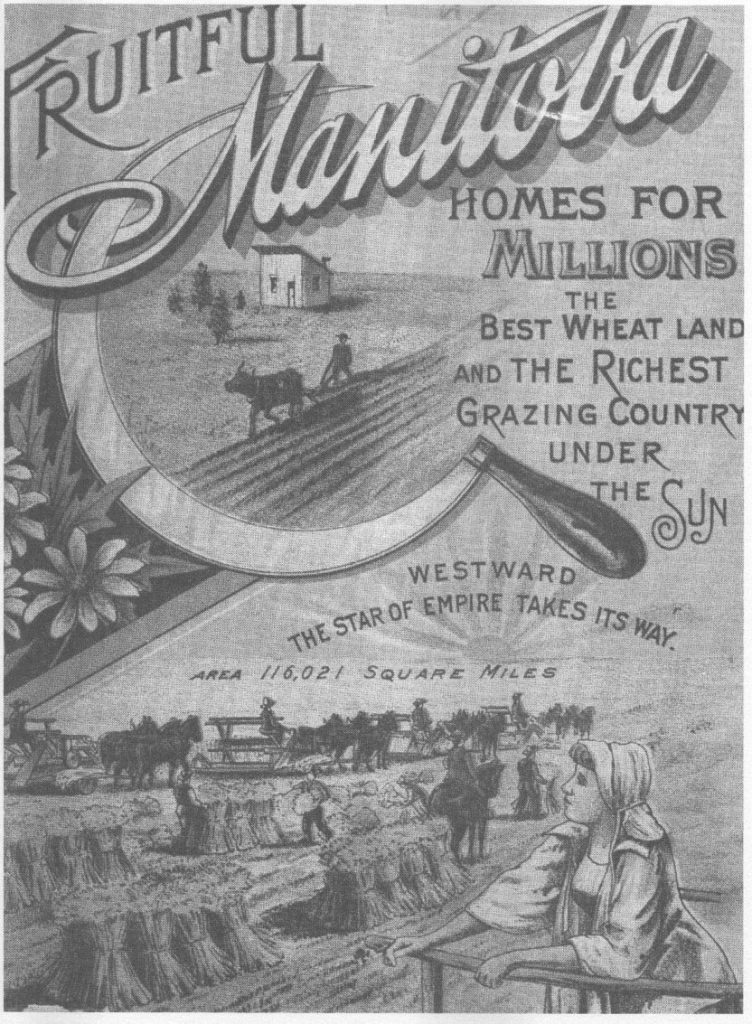

As the years went on, Red Fife seeds were spread around Canada and the northern United States’ crop-growing regions. By the time Red Fife reached Manitoba in the late 1800s, it was a force to be reckoned with. It grew in Manitoba better than anywhere else in Canada or the United States. “Suddenly it had become, by all accounts the finest wheat in the world for milling bread flours,” wrote historian G.N. Irvine.

The variety’s reputation spread like wildfire. Minnesota started importing Canadian Red Fife and marketing it as a premium product over its locally grown Minnesota Red Fife wheat. According to the Canadian government, 580,000 acres of grains were grown in Western Canada in 1885, which exploded to 13.6 million acres in 1910, including 7.6 million acres of spring wheat alone. Canada’s Grain Inspection Act of 1885/86 decreed that any wheat hoping to receive top grade must be primarily Red Fife.

The Canadian West had been secured and solidified by Macdonald and the influx of European immigrants, and wheat production skyrocketed. Across the Prairie provinces, 2.8 million metric tonnes of wheat were produced in 1906.

Although it was the best wheat variety Canada had ever seen, Red Fife’s long maturity period was problematic for farmers. Many wheat crops fell victim to killing frosts in the fall as farmers waited for the crop to mature. The need for a quicker-maturing wheat crop became more pronounced when wheat production spread further north and northern farmers had even more trouble growing Red Fife due to a shortened growing season—up to 15 days shorter in some cases, compared to southern farms. In this case, the English proverb, “necessity is the mother of invention” proved to be apt.

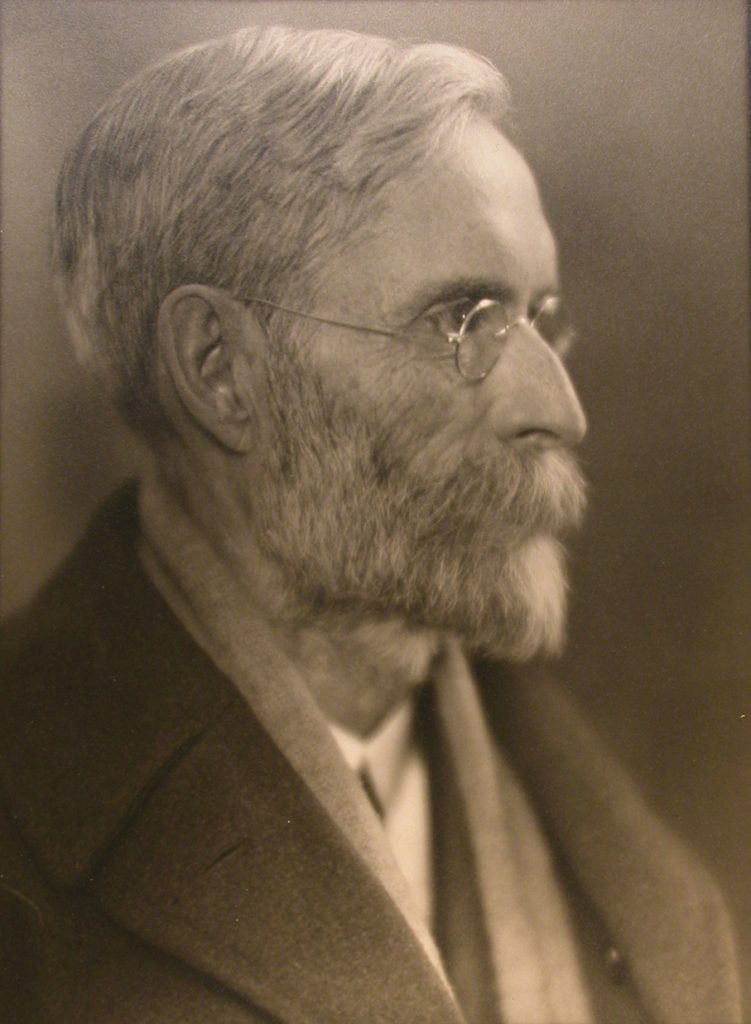

A man named William Saunders was put in charge of the country’s brand-new experimental farms, where research would be conducted to find Red Fife’s successor as the premier Canadian wheat variety. Saunders was Canada’s first appointed dominion cerealist. One of his duties was to create a wheat variety that had all the positive traits of Red Fife, namely milling quality and yield, but with a shorter maturity period to escape killing frosts. He sent his son, A.P. “Percy” Saunders, to create crosses at the three Prairie experimental farms, and the young Saunders did not disappoint. The ubiquitous Red Fife was paired with Hard Red Calcutta, a wheat variety from India lauded for its early maturity (six days faster than Red Fife). By crossbreeding the two varieties in 1892, Percy unknowingly wrote the next chapter in Canadian agricultural history, but it would take more than a decade for anyone to realize the magnitude of his success.

ORAL HISTORY

Percy’s brother Charles was, by all accounts, a black sheep not the least bit intrigued by agriculture. Born the year of Confederation, Charles was gifted with an ear for music and had grand ambitions to be a flutist like no other. His father, however, had other ideas for his son. At William’s insistence, Charles begrudgingly studied science and eventually moved to Baltimore where he earned a PhD in chemistry from John Hopkins University in 1891. Upon graduation, Charles still had precious little interest in chemistry. He and his mezzosoprano wife, Mary Blackwell, ran concert and recital studios in Toronto, taught music lessons and regularly contributed a music column to The Week magazine. City living was good for Charles.

However, William, a close friend of then-Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, simply wouldn’t let his son continue in the arts. In 1902, much to Charles’ shock and dismay, his father sent him a letter informing him that he had been appointed a dominion cerealist at Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm. Not wanting to incur any more of his father’s wrath, Charles mournfully moved from Toronto to Ottawa to begin what surely must have felt like exile.

Upon arrival in 1903, Charles was faced with the unenviable task of sifting through genetic wheat crosses created at various experimental farms in the hopes of identifying one to replace Red Fife. Eventually, he dusted off a sample from a name he recognized: A.P. Saunders, his brother. The sample was labelled “Markham,” which Charles later renamed “Marquis.” Perhaps it was nepotism, perhaps not; either way, Charles took a closer look at the sample.

He gathered Marquis and a number of other crosses as he began to investigate their utility. There was only one problem: it was winter and he had no lab for chemistry, no mill for flour production and no oven for baking. So, Charles improvised. According to historian Stephan Symko, “… he would take a few grains from each stalk, chew them and decide on their probable flour and bread quality on the basis of the dough created in his mouth.” Charles himself said of the process, “I made more wheat into gum than was made by all the boys in any dozen rural schools.” He figured if his teeth could substitute for a mill and his mouth for an oven, he’d get results soon enough, wrote Symko.

Charles must have had an educated palate because Marquis was put forth as Charles’ top choice of wheat following his oral investigation. His work gained such importance that he was eventually knighted and given a $5,000 annual pension from the Canadian government in his later years.

By 1907, as Marquis seed samples proliferated, they were sent to Indian Head, SK, for further tests and propagation. From Indian Head they were sent to Brandon, MB, in 1908, before being made public to farmers in 1909. Marquis had a trifecta of qualities that made it superior to Red Fife: early maturity, high yield and strong straw that kept the crop from lodging (when a crop falls over in the field, reducing quality and complicating the harvesting process). Farmers were ecstatic and so were grain buyers, millers, bakers and customers.

In 1914, Marquis migrated south to the United States. It only took one growing season for Yankee farmers to be converted. When the Great War ended in 1918, more than 20 million acres of Marquis were grown in North America. The crop value of Marquis in Canada alone in 1918 was US$259 million. Combined with the four major crop-producing American states of Montana, the Dakotas and Minnesota, Marquis’ total crop value was US$629 million.

Marquis dominated the landscape in Canada and grain-heavy American states for more than 30 years following the First World War. Even though it was the Canadian government that received credit for its Marquis, Charles said it was “God Almighty” who was responsible for the variety’s success.

Americans took note of Charles’ unheralded contributions to agriculture, as well. “The greatest single advance in wheat ever made by the United States was the introduction of that class of hard spring wheat known as Marquis wheat. The idea came to us free of charge from the Dominion of Canada’s Cerealist, Sir Charles E. Saunders,” said James Boyle, former U.S. secretary of agriculture.

THE NEXT GENERATION

In 1918, 14 million acres of spring wheat were planted on the Prairies, with Saskatchewan accounting for 9.1 million of those acres. However, the need for new varieties continued in the West. Eventually, Marquis’ reign came to an end, as farmers had to work harder to prevent diseases and abiotic stresses, such as wind, rain, hail and snow, from destroying their farms. Since Marquis was a quintessentially Canadian invention, it was the United States’ time to return the favour.

University of Minnesota wheat breeders eventually created a spring wheat variety called “Thatcher” in 1935. It was very similar to Marquis, but had greater fungal resistance and matured even earlier. Slowly but surely, Canadian acres seeded to Marquis were converted to the new variety. But in 1953 alone, 3.5 million acres of cropland were lost due to disease pressure. A new wheat line called “Selkirk” was released as an immediate response, which managed to reduce incidences of disease in the short term.

A short-lived but high-performing variety named “Manitou” appeared in 1965 for a few years before it was overshadowed by the next big breakthrough in 1969. Developed in Winnipeg, “Neepawa” had all the trappings of a winner: high yield, high protein, strong disease resistance and wide uptake by Prairie farmers. In fact, Neepawa made history in 1980 when it was declared that it had replaced Marquis as the new standard against which all other wheats would be measured. It was the second time in Canada’s history a wheat variety surpassed an established line in terms of all-around quality.

MODERN DAY

Today, there are thousands of varieties of wheat grown around the world. However, on the Prairies, there are still fewer than a dozen varieties that are grown in large quantities each growing season.

For many of those varieties, Canadians can thank Ron DePauw, a mild-mannered, 73-year-old former wheat breeder from Kamsack, SK. If you’ve eaten any bread product in Canada over the last few decades, there’s an extremely high chance it was made with a wheat variety he and his team created in the Swift Current test fields during his long and illustrious career.

DePauw is considered to be one of Canada’s top wheat breeders of the last 50 years. He developed a love of the natural world early in his life and has spent more than four decades dedicated to public breeding research with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. His goal from the outset was simple: “When I started working at Beaverlodge [Alberta] in 1973, I had set myself a personal goal of wanting to develop really good varieties that would grow successfully on farmer fields, and farmers would be satisfied to grow them again,” he said.

By all accounts, DePauw succeeded. One of the most notable contributions was in 1993 with his team at the Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre (SPARC)—a CWRS wheat variety called “Barrie” that boasted high yields, high protein, disease resistance and wide adaptation for the Prairies. Not only that, it had shorter, stronger straw to stand up to the abiotic stresses and adverse conditions common across the Prairies.

“It was the first product that broke the yield and protein link,” said Todd Hyra, business manager for Western Canada at SeCan, a Canadian seed company. “Normally, when protein goes up, yield goes down. In this case, both were high.” It didn’t take long for farmers to take note of this novel innovation. Barrie quickly became the dominant variety grown on the Prairies from about 1996 to 2005, hitting a peak in 1999 with a share of 47.5 per cent of all CWRS acres.

Less than a decade after Barrie’s creation, DePauw produced “Lillian,” another CWRS variety with a high yield, a solid stem and a greater resistance to a damaging pest known as the wheat stem sawfly. Lillian took a turn to unseat Barrie and was the major variety from 2007 to 2010 in Western Canada. “It’s one thing to try something, but if [they] repeat growing them, that’s a measure of success that farmers are satisfied,” said DePauw of his varieties’ uptake.

That success has come from decades of institutional hard work and dedication, according to Hyra. “I was in a field with him last year in southern Manitoba, the temperature was in the 30s, it was humid … he was trekking through it like he was 25 years old. I can’t imagine what he was like when he was younger.”

According to certain plant breeders, having one wheat variety as successful as Barrie or Lillian to their name would allow them to retire happy. Breeding research is painstaking work and discovering “the one” is far trickier than finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. Bringing the average new variety to market typically takes about 10 years, and it’s not a guarantee it will gain market acceptance, either. However, DePauw and company defied the odds and many of their greatest hits can be found in fields all across the Prairies. In total, DePauw and his team registered more than 65 higher-performing wheat and durum wheat varieties, such as Brandon, Carberry, Kyle and Stettler. DePauw himself is listed as the lead breeder on 29 different CWRS varieties. DePauw estimates the team at Swift Current has spent more than 500 collective years breeding wheat during his tenure.

Much of that work wouldn’t be possible without the average farmer directly contributing to the success. Western Canadian farmers voluntarily pay for research funding through levies, also called check-offs, on their grain sales. That money is used for funding public research, an immeasurable contribution, said DePauw. “That money we got from producers had a very, very big impact. It allowed us to double our genetic gains and enabled us to double our breeding program. Farmers are big time investors of this.”

The work DePauw has done throughout his entire career was, is and continues to be acknowledged by farmers. According to DePauw, 40 to 50 per cent of seeded CWRS acres are breeds that originated in Swift Current.

“This was only possible through having an incredible team at SPARC. You have all of these amazing people who contribute to this. It gets to be very complex,” said DePauw. “It’s mind-boggling the amount of effort that goes into something like this.”

WHEAT WORLDWIDE

The majority of Canada’s annual wheat crop is exported to countries around the world. Canada’s sterling reputation for consistency and quality is what attract international buyers to our grains.

“It really goes back to what the consumer wants. Our consumer wants big, beautiful, soft bread that also has strength and butterability, or crumb strength,” said Adam Dyck, the program manager for Warburtons in Winnipeg. The U.K. bakery is only slightly younger than Canada at 140 years of age, and for each and every year it’s been in business, it’s used Canadian wheat. “We’re a premium brand in the U.K., quality is what we’re known for,” said Dyck. “The Canadian wheat that we source is the backbone to that quality and the consistency that we’re able to deliver with every shipment to the U.K. That’s in every loaf of bread.”

Each year, Warburtons purchases 200,000 tonnes of Canadian wheat that is grown by 600 different Prairie farmers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. That top-quality Canadian wheat is blended with a lower-quality U.K. winter wheat in order to create a grist, or flour, that will satisfy customer demand.

With more than 100 products using Canadian wheat, such as crumpets, pan bread, sandwich thins and wraps, it’s the diverse varieties grown in Canada that afford Warburtons the ability to branch out and experiment with its products. “What the Canadian wheat offers us is the ability to try new things,” said Dyck.

JoAnne Buth is the executive director at the Canadian International Grains Institute (Cigi) in Winnipeg where her organization works tirelessly to promote wheat worldwide. In her mind, Canada’s storied wheat quality comes down to two things. “When we talk about the quality it’s the gluten, both the strength and extensibility,” she said. “You’ll see other wheats that are stronger, but don’t have the extensibility. If you’re pulling on something, you want it very elastic.”

Aside from the milling and baking characteristics, the colour of wheat is just as important to international grain buyers and consumers.

Canada Western Amber Durum wheat has been bred to have a vibrant yellow hue, popular among North African countries, such as Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, where couscous reigns supreme. The colour is a novel adaptation by Canadian durum breeders over the last 25 years who developed specific varieties resulting in the distinct colouration when compared to historical varieties. The three nations alone imported a combined 1.85 million metric tonnes (MMT) of wheat last year. “Colour is so important for their couscous and pasta products, they want a bright yellow colour,” said Buth. “The Canadian product is highly valued.”

Other top markets for our durum include Italy at an average of 900 MMT, the U.S. with 381 MMT and Venezuela at 300 MMT. Our bread wheats have an even larger and more diversified market base, such as Japan with 1.4 MMT, Indonesia at 1.28 MMT, Bangladesh at 916 MMT, Colombia at 837 MMT and Sri Lanka at 591 MMT on average each year.

With wheat an essential part of people’s daily bread both in Canada and around the world, it is a homegrown success story that all began with perhaps the most unlikely hero, Charles Saunders. In their book, The Canadian 100: The 100 Most Influential Canadians of the 20th Century, historians H. Graham Rawlinson and J.L. Granatstein wrote of Charles: “Saunders made possible the prosperity of the Prairies, and he is entitled to stand first among the most influential Canadians of the century.”

Comments